Who was C.O.B?

How a pair of World War One binoculars revealed an officer’s story.

Every object has a story to tell and, if you are lucky, they will give up their secrets in sometimes surprising ways. An “I thought you might like these’ gift some years ago from what I believe was a house clearance, these standard British World War One binoculars on closer inspection, bore tantalising clues to its owner and then a hidden secret that was the key to unlocking the full story.

Binoculars were a crucial piece of equipment for the British military in World War One. Produced by various manufacturers during WWI these No. 3 Mark I prismatic binoculars are marked Hutchison, London 1915 with a magnification of “6”. The serial number is 7353.

Two factory-engraved broad arrows, together with roughly engraved facing broad arrows to possibly show the equipment was decommissioned appear on the back plates. “C.O.B.” is scratched on the centre of the hinge. There are also extremely faint scratched battle names to the front of the binoculars – CAMBRAI, LOOS, YPRES, SOMME. Similarly, on the rear plates of the binoculars – C. O. BENDING is scratched on the left and C.O.B on the right.

The leather case is stamped “CASE NO. 3 PRISMATIC BINOCULAR. J.B.BROOKS & CO. LTD”. The case is, therefore, not original to the binoculars.

Scratched on the leather case is “C.O.B. XI MMG Bt”. Again, faintly scratched battle names include “YPRES” and “LOOS”.

Right at the bottom of the case was a pad of blotting paper, beneath which was the answer to who C.O.B. was – a cutting from headed notepaper which tells us our man is Charles Oscar Bending.

Some light research reveals Charles was born in Hampstead on 25 December 1892, the son of Charles and Gertrude Bending. The 1901 Census tells us his father was an Inspector of Weights & Measures and the family lived at 25 Maygrove Road, Hampstead. At this time Charles had three older sisters, Gertrude Mary Bending, Beatrice Annie Bending, and Emma Bending Bending (yes, really), and a younger brother, Robert Ernest Bending. At the time of the 1911 Census Charle and all his siblings (other than Emma) were employed as Insurance Clerks.

Charles joined the 28th London Regiment on 29 December 1914, as a Private (Regimental No. 2171). He was appointed 2nd Lieutenant Machine Gun Corps No 4 Bty on 15 September 1915 and was made Lieutenant 3rd Motor Corps, Machine Gun Corps in October 1917.

At 28 Charles married Beryl Wilson Stenson (26) on 18 June 1921 at the Parish Church, Wimbledon. He was living at 50 Cronhurst Road, Cricklewood at the time and is listed as a Civil Servant. He was an Inspector of Taxes. We have found one daughter, Gillian Elizabeth Bending. We have also found a record that we was MC 2nd Lt Essex Territorial Army – responsibility for Cadet Corps., 15 January 1945

Charles died in 1975 aged 82 at 17 Bakers Lane, Braiswick, Colchester.

The Motor Machine Gun Corps

Formed in 1914, the Motor machine Gun Service was a unit of the british Army in World War I which consisted of batteries and motorcycle/sidecar combinations that were armed with Vickers machine guns. Highly mobile, and particularly effective in the early, more fluid, stages of the war, their usefulness reduced as the conflict bogged down into the stalemate of trench warfare. The corps was incorporated into the Machine Gun Corps in October 1915 and the Machine Gun Corps (Motors) and again came into their own with the surviving mobile batteries during the advances of 1918.

Image: Imperial War Museum – IWM Q 9003.

SIDE STORY

The World War One Glass-Rubber Exchange

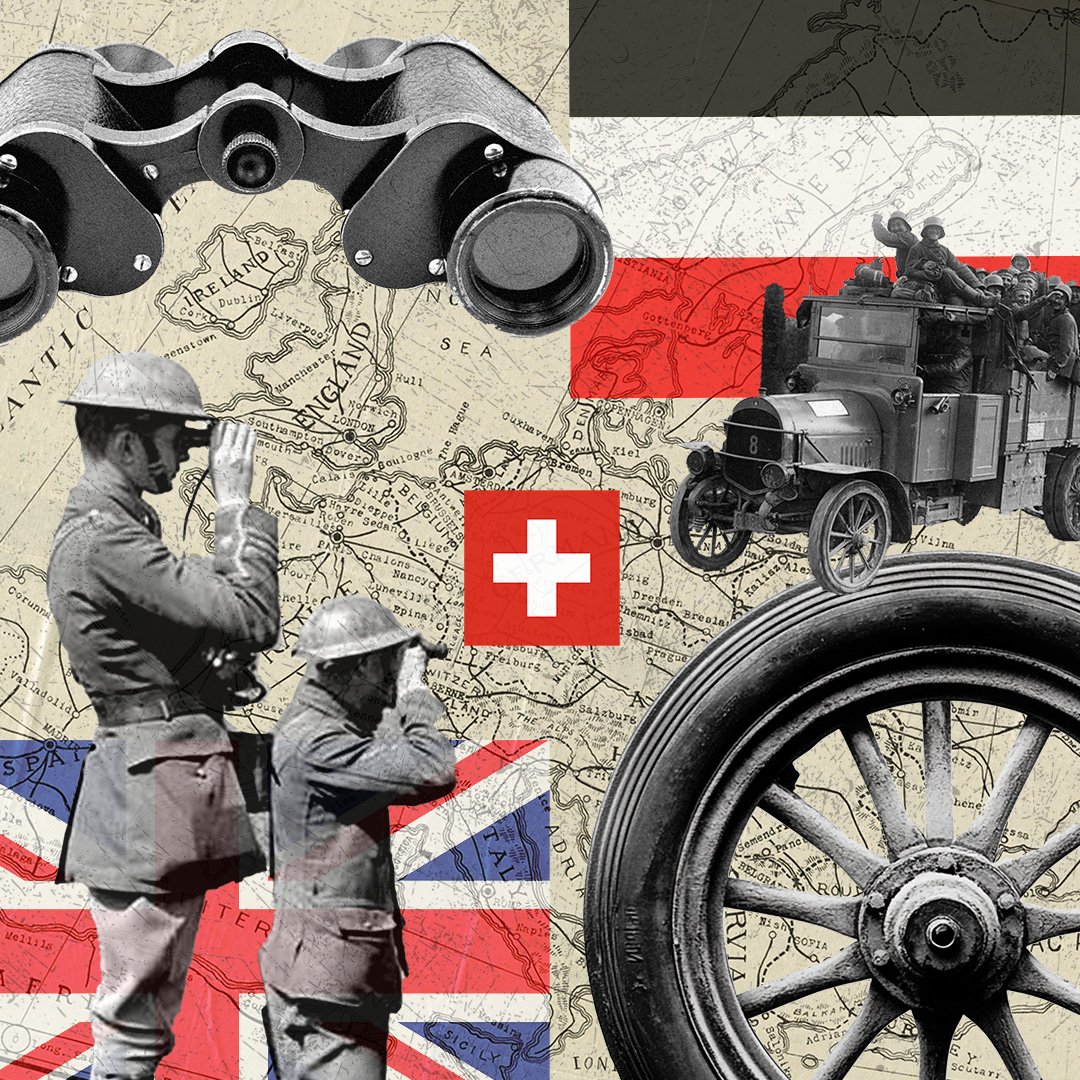

Image: © historyreunited.org / Hunter Gatherer Ltd

During World War One, the glass-rubber exchange between Britain and Germany was a crucial wartime agreement initiated around 1915. This arrangement emerged from the dire need for essential materials that both nations faced due to blockades and resource shortages. Britain, heavily reliant on glass for medical supplies, optical instruments, and scientific equipment, found itself in a precarious position as German glass manufacturers were among the best in the world. Conversely, Germany faced a critical shortage of rubber, vital for military vehicles, aircraft, and other war-related machinery, due to British control over global rubber supplies.

Binoculars were especially vital on the Western Front, where trench warfare dominated. Officers and soldiers relied heavily on binoculars to scout enemy positions, observe troop movements, and direct artillery fire. The exceptional quality of German glass made their binoculars the best in the world, a must-have for British forces trying to gain any advantage in the grueling stalemate.

Switzerland played a vital role as an intermediary in this exchange, leveraging its neutral status to facilitate the transaction. Swiss diplomats and commercial entities helped broker the deal, ensuring that both parties adhered to the agreed terms despite the ongoing conflict. Swiss banks and transport companies managed the logistics, overseeing the safe transfer of goods across borders. This intermediary role was crucial in maintaining a semblance of trust and ensuring the smooth operation of the exchange.

The agreement remained a unique episode in the economic history of World War One, showcasing an intricate balance between conflict and co-operation, with Switzerland’s neutrality proving instrumental in its execution. By early 1916, British investment and technological improvements had increased production of optical glass such that any need for an exchange was removed.

If you have any information on Charles Oscar Bending or the Machine Gun Corps in World War One that you think may add to this story, then please get in touch.